Slidell, to the contrary, was in better condition than I expected. Slidell is a suburb about thirty miles outside of New Orleans. Apparently only the southern part of Slidell by Lake Pontchartrain was hit hard. Where we stayed reminded me of Sunrise Highway on Long Island – a busy road lined with strip malls, gas stations, and chain restaurants. There was a Shonee’s, a Cracker Barrel, The Outback, and, of course the fast food hamburger joints. Not too many local restaurants, though. We were looking for some of that Cajun, Creole cooking and finally found Copeland’s of Louisiana, which was a Louisiana chain like TGI Fridays. It had good catfish and was the closest we could get to authentic Louisiana cuisine. They had just opened a month ago after being closed most of the year to renovate after Hurricane Katrina.

The convenient stores at the gas stations in Slidell sold a proportionally high amount of liquor and cigarettes. I couldn’t find yogurt or cheese or some of the usual things I buy in my 7-11 in New York. I searched three convenient stores before I finally found anything remotely nutritious for breakfast the next day. The gas station convenient stores showcased beer, wine, and all sorts of hard liquor. My friend said, “Wow, they’re really trying to push the liquor on these people. Sometimes I think they do that to keep people down.” We see a sign: “Drive thru – daiquiris.”

Slidell’s population has increased from about 35,000 last year to over 100,000 today at least according to our Habitat for Humanity hosts. I can’t imagine how the schools are coping with such a sudden increase in population. The East Tammany Habitat for Humanity’s goal is to build 100 houses by June 2007. Prior to Hurricane Katrina, they averaged two to three houses a year.

We, the Habitat volunteers, were housed in a Church facility together with Americorps volunteers. Americorps managed the Habitat projects together with a few permanent Habitat employees. It struck me as strange that government employees were being housed by a church. To me it raised some church-state issues even though I do support Habitat for Humanity’s valiant effort to build new homes for people in New Orleans and surrounding areas. “Americorps” is like a peace corps for the United States. Young 18-24 year olds get assigned community service projects throughout the country where there is high need. This group thought that they would be traveling the mid-west, but after Katrina hit they were all sent to the Gulf Coast. The group of Americorps kids was impressive -- mature, responsible. They knew their jobs and did them well. Two young women in their twenties were in charge of teaching 25 or so volunteers with little experience how to build frames for concrete foundations. They taught us a whole new vocabulary, as well as, new skills. Our frames needed to be “flush” and “plumb.” They taught us how to use a level, how to sledge a stake, how to hammer in “kickers.” They demonstrated great management techniques, motivating everybody, making sure everyone was included, correcting mistakes in a kindly manner, and encouraging good work. They were detail oriented and expected the job done right. If it wasn’t, it had to be done over. Another “Americorp” kid sawed all the wood for us. (I was grateful because the suburban princess does not use power tools ...yet!). These young people work five to six days a week, eight hours a day in the hot Louisiana sun. In addition to their work week, they are expected to do a certain number of volunteer hours. When we, Habitat volunteers, were celebrating the completion of our work week, we learned that our Americorp manager would have to spend her Saturday picking up garbage. For all this, each member of the Americorp brigade gets paid $150 a week. They get housed in the church dorm and get lunch daily. For breakfast and dinner, they are on their own. One kid wanted to leave the Gulf, “I can’t do anything fun here,” he said, “I go into New Orleans once and that’s half my paycheck.” I told them they need a union bad. Everyone laughed, but I was serious. One day I asked my Americorp manager, “Are you guys pretty much in charge of rebuilding New Orleans or are other government agencies doing stuff, too?” “I don’t know,” she said,”I only know what Americorp is doing. I think FEMA might be doing some building, but I’m not sure.”

Working together to align frame.

We also hammered together the boards for the frame.

We also hammered together the boards for the frame.

This corner took all morning to do.

This is what the frame looks like when complete.

Happy future home owners worked hard with us.

The trouble with working with an all volunteer staff is that they are often inexperienced and as soon as they learn the job they have to leave. Also, sometimes there are mistakes as one group takes over where the previous group left off. We had to redo two of our wall frames because of these types of errors. The Habitat people told us that it generally takes about fifteen weeks to build a house from beginning to end if you have enough volunteers. Not bad, at all, I thought, knowing that it took almost that for my husband and I to get our house painted. One fellow who lived in Atlanta and volunteered with the Atlanta Habitat for Humanity said that the Atlanta group has more money than volunteers so they sub-contract out a lot of the work. The East Tammany Habitat has volunteers, but no money. Fifteen weeks with volunteers and you have a house. Imagine how much faster it would be with professionals – with the Army Corps of Engineers or with work programs like the ones FDR created to get us out of The Depression. It’s been a year since Hurricane Katrina. Why has so little been done?

The French Quarter, because it is above sea level, is fine. It is beautiful and I was surprised, jaded traveler that I am, how much I feel in love with it. Spanish and French architecture, iron trim balconies, and gas lanterns decorate narrow streets. I became smothered by the sounds of zydeco, jazz, blues, rock and raptured by the Cajun and Creole spices. It is an aura unmatched anywhere in the United States.

My husband and I were lucky to catch the annual Satchmo Jazz Festival with live bands scattered throughout the French market area. The crowds were small, but intimate, bonded by their love of the New Orleans culture. Even in the rain, people stayed to dance and sing.

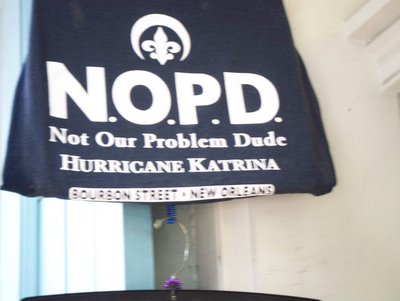

The festival resisted what many perceive to be an attack on or threat to the New Orleans culture. The anger at our government is evident. Signs hang from balconies, “Thanks to global volunteers. No thanks to federal government.” T-shirts in souvenir stands express anger at FEMA’s response: “FEMA: Fix Everything My Ass” is just one example. Signs for condos hang on almost every street throughout the French Quarter and some worry that high priced condos could lock locals out of their own housing market.

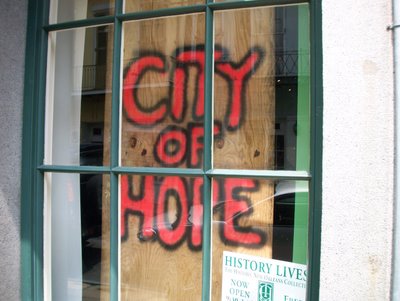

Yet, there is also of hope and determination that the culture of New Orleans will survive. “New Orleans Renaissance” banners flutter from lampposts throughout the Quarter. Other t-shirts emblazon inspirational sayings, “Rebuild New Orleans” and “Hope.” Restaurants and businesses with “Open” signs in their windows take on new meaning in New Orleans. Other signs announce, “We’re coming back!” The people in New Orleans are survivors and each in his or her own individual way is fighting for the survival of the home and culture that each knows and loves. A female singer at the jazz festival sings Aretha Franklin, “Think! Think about what you’re trying to do to me.” The drummer sings Marvin Gaye, “What’s going on? What’s been going on?” A jazz parade honoring Louie Armstrong plays, “Stand by Me.” One of the musicians in the parade, a member of the Dumaine “Street Gang,” tells me, “This is natural New Orleans. Katrina can’t stop nothin.’ ” These heroes need our support. They need more than smattering of good hearted volunteers.

Please watch the videos. They are amateurish, but will touch your heart.

Please watch the videos. They are amateurish, but will touch your heart.What's going on?

Think about what you're trying to do to me.

Community sings "Stand by Me."

Stand by Me with awesome dancing.

Katrina can't stop nothin'